It was June and I was still residing on Steve’s couch. I was paying him rent for it, approximately. I was self-employed and ran a small sticker-design business from the right end of the couch and the end-table adjacent where I kept my markers, but since I’d run out of sticker-backed-paper in November and Staples wasn’t carrying it anymore, I’d suspended operations indefinitely. Steve was a bagger at Star Market, thinking about going back for his Ph.D., and had figured out how to steal cable from the landlord, so there was always something to talk about between the crazy customers and what was on TV. Sometimes we talked philosophy. We didn’t have girlfriends anymore. Things were great.

We sat in silence for a while, watching the history of sitcom entertainment evolve through the decades from black-and-white to color on TV Land. Eventually the sun started to sink over the high-rises near the river. Steve sniffed.

“Remember when we were kids, man?” I said, pointing at the TV. “Like Jetsons.”

Steve said, “Right.” We were watching Rhoda. I was still thinking a few shows back.

“Not like this is,” I said. “I mean like I know what this is, what we’re watching.” I meshed my fingers together. “The ladies sort of remind me of each other, Rhoda and the Jetsons mom, so my mind made the leap. What I’m saying is, when we were kids we were told the future was supposed to be so technologically advanced with all kinds of Space-Age shit—like, we’d be living in the sky and whizzing around on jet-packs?” I made a slight waggling hand gesture that I hoped would express the joy of creation and the sorrow of a species not meeting its genetic and spiritual potential in the universe yet conscious of its own self-limiting march to mediocrity, sated on unhealthy entertainment and sick food and an apathetic attitude toward community and one’s place in the scope of human achievement. I talked about things like this a lot with Steve. “But we don’t have fucking jet-packs. We don’t. What happened to the jet-packs?”

“Actually, we do,” Steve said. From behind his end of the couch he hoisted a gleaming chrome device fitted with buckles and leather straps and, along the bottom, a cluster of vents.

“Is that a jet-pack?” I said.

“Yeah.” Steve stood up for the first time in hours. His knees cracked. He shrugged the jet-pack onto his shoulders. He indicated the left shoulder strap with his chin. “Can you, uh—tighten this for me a little?”

I stood and tightened the strap. Steve wriggled his shoulders into the jet-pack to test the fit and fluid sloshed inside. I saw my reflection in the bullet-shaped chrome spire that rose to just above his head.

“Wow,” I said. “Where’d you get it?”

“The future,” Steve said. He hiked his chin at the breakfast nook, where we’d left our unwashed cereal bowls from lunch, and there was a golden spray-painted football helmet embedded with three dials along the right side. I didn’t recall seeing it there before. “That’s a time machine. I built it. And this,” he said, cocking a thumb at the nosecone of his jet-pack.

“You built it?”

“Yes. Way in the future, when I developed the technology to make jet-packs possible and feasible. But I came back.”

“OK,” I said.

“I’ve actually been to the future and back several times now.”

I looked over at the helmet. “When?”

“Just now.” Steve nodded to me, chuckling to himself. “It’s difficult to explain, but such is the nature of time travel. For the traveler, time travel is a long journey, one that’s physical and mental and emotional. But for those left behind it’s instantaneous—as if nothing has happened.” I blinked. Steve was suddenly holding the football helmet.

“Right,” I said. I looked at the helmet, then again at Steve. “How come you never let me in on this before?”

Steve fished around on the right side of the jet-pack and produced a small cabled ignition switch, which he clipped to the front of his sweatpants. “Doing that now, right? You see, words like ‘before’ don’t mean anything. Time’s pretty much irrelevant to me now,” Steve said. “It doesn’t make sense from my point of view to describe it to you chronologically, since I now exist outside of linear time. But since I’ve started my travels, I’ve seen the far reaches of the past, and I’ve seen the future. Far, far into the future—farther than you could comfortably comprehend.”

“Give me a—fuck’s that supposed to mean?”

“To me, it’s all the present—the past and the future. And with this”—Steve patted the side of the jetpack gently, his watch striking the metal with a hollow ring—“I’m no longer even tethered to the earth.”

I snorted. “So, right. OK. Wait.”

Steve gazed at me patiently, polishing the top of the football helmet with a sleeve. He glanced at his wrist. “I’ve been here before, Nate. In 4.6 seconds, once you’ve finally spit it out, you’re going to ask me if I’m really traveling through time why I still wear a watch.”

I gave it a moment’s thought. “That’s totally true,” I said.

“Because when I get somewhere, I still have to know what time it is.”

“Makes sense.”

“See, Nate—I often come and I go, existing among the shadows of my past, experiencing life as the wretched man I was, the man before I went back for my Ph.D. and eventually experienced my moment of transcendence. Which, to be honest, began here, realizing I’d done nothing with my life so far, the lowest point of my life emotionally and listening to you go on and on about something or other every morning and afternoon and night. I realized one day with you occupying half my couch that I had to do something with my life to transcend my miserable state or give up entirely. Today was that day.” Steve sighed, looked around the apartment nostalgically. He glanced at a pile of my laundry on the floor. I couldn’t remember if it was the clean pile or the dirty pile. “Sometimes I like to come back here and remember the depressing morass I was in, as it’s the only frame of reference I have to gauge the scope of the paradise and total freedom I now enjoy traveling through the aeons.” Steve laid a hand on my shoulder, almost fatherly, although he was much shorter than I was. “You can have the apartment and whatever’s in the owl.” The owl was a ceramic figurine given to Steve by his grandmother, where we anted up spare cash for pot, food, and other incidentals.

“Um,” I said.

Steve slipped the football helmet on his head, fitted the chin strap, and spun the dials along the side randomly. As he crossed the room to the window I saw he’d attached tiny glistening solar panels to the back. Steve raised the window and screen, letting in a rush of street noise.

“Steve?” I asked, frozen in place but trying to will myself forward to seize his arm. “You’re not going to—” I thought about the traffic below. We were nine stories up. “Were you gonna—what I mean’s, like … are you going to be back? Should I, like, expect you back later tonight?”

Steve put one knee on the windowsill.

“At some point?” I said.

Steve cast a gaze outside the window. “I’m going where the universe leads me,” he said, “and at this point, I am The Universe.” He threw a switch on the jet-pack and it whirred softly to life, a gentle wind from its vents stirring my papers and rolling pens to the floor. “One thing: about that new job? Don’t take it. You may not believe me now, but just don’t. Trust me.”

He tapped the ignition button and the jet-pack revved briefly, roaring alive in a burst of harmless cool blue flame licking the wood floors.

“Which new job?” I shouted.

“Oh,” Steve said. “You may not have done that yet. What day’s this?”

I looked out the window, then helplessly back at the cereal bowls, then at Steve. “Uh…”

He waved a hand at me dismissively. “You’ll find out!” Steve said.

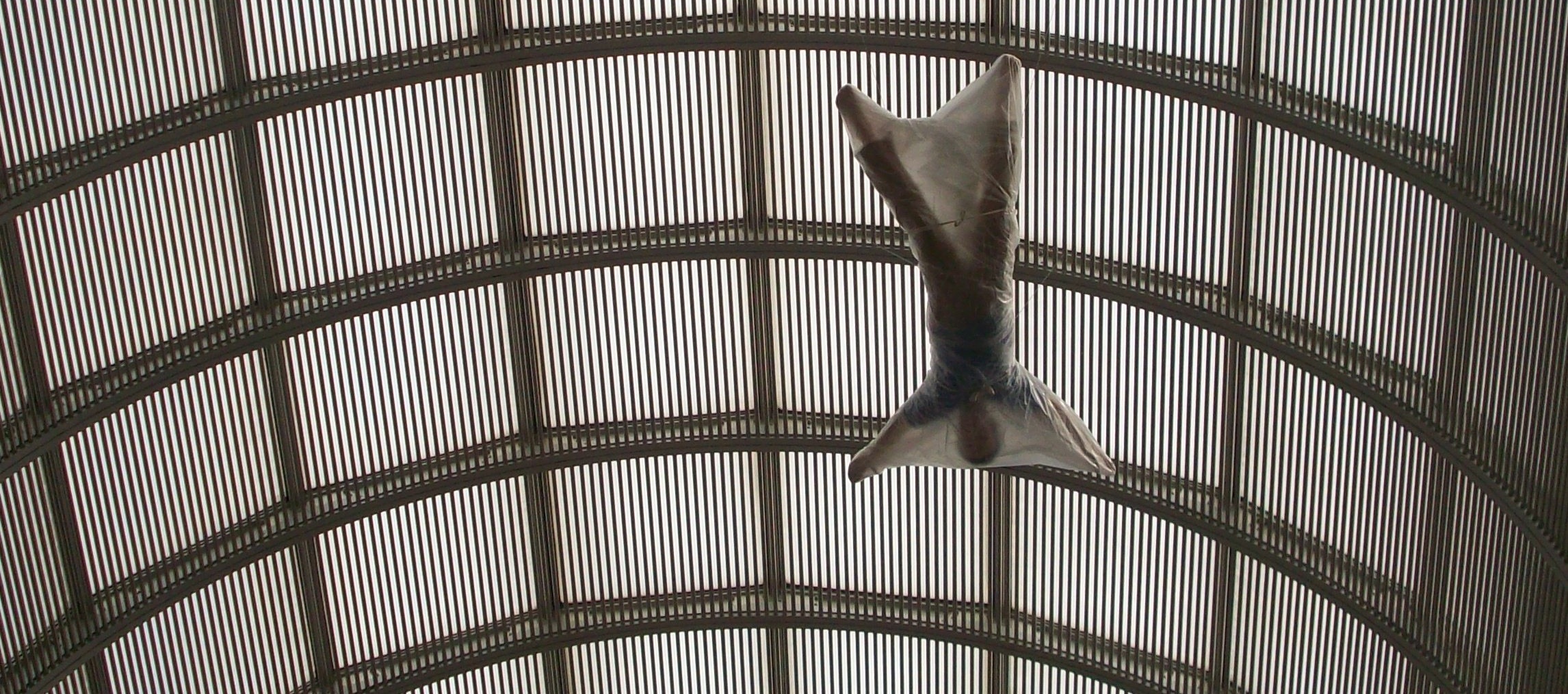

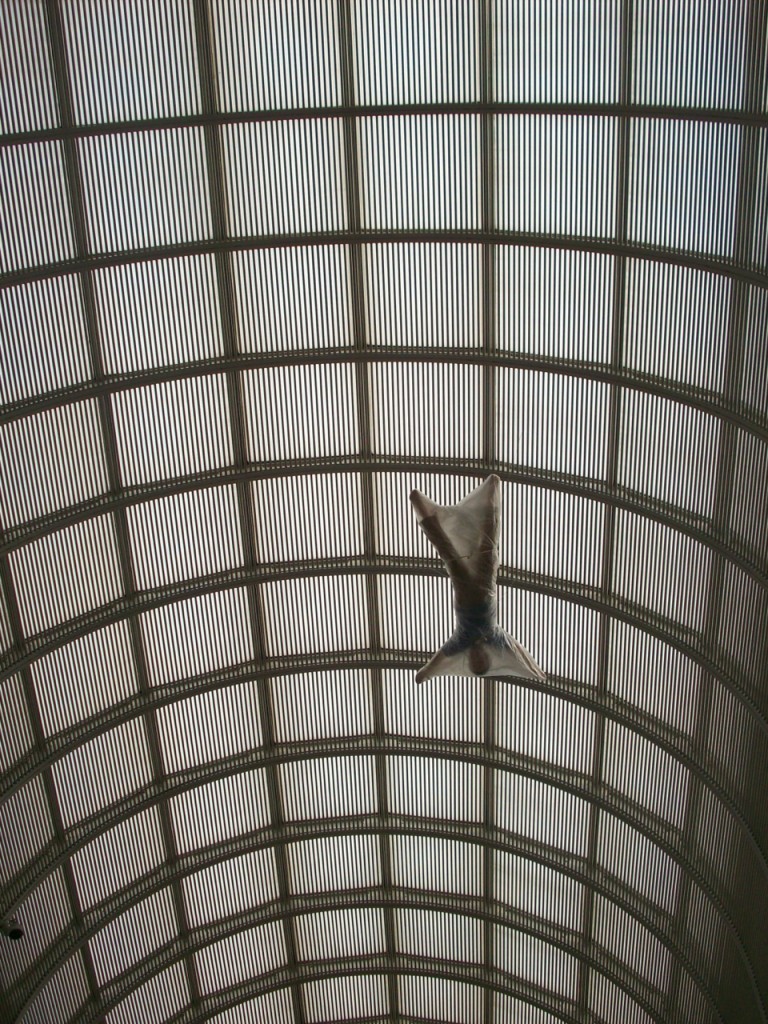

Bracing the football helmet on his head, Steve leapt out the window into the city below. I tripped against the side of the coffee table and stumbled to the window, and saw outside that Steve had shot himself far into the distance, over the streets and the park, above the river, soaring higher into the air with ease, his arms outstretched like a dancer, becoming a small glowing blue dot against the darkening sky.¶

Leave a Reply